-40%

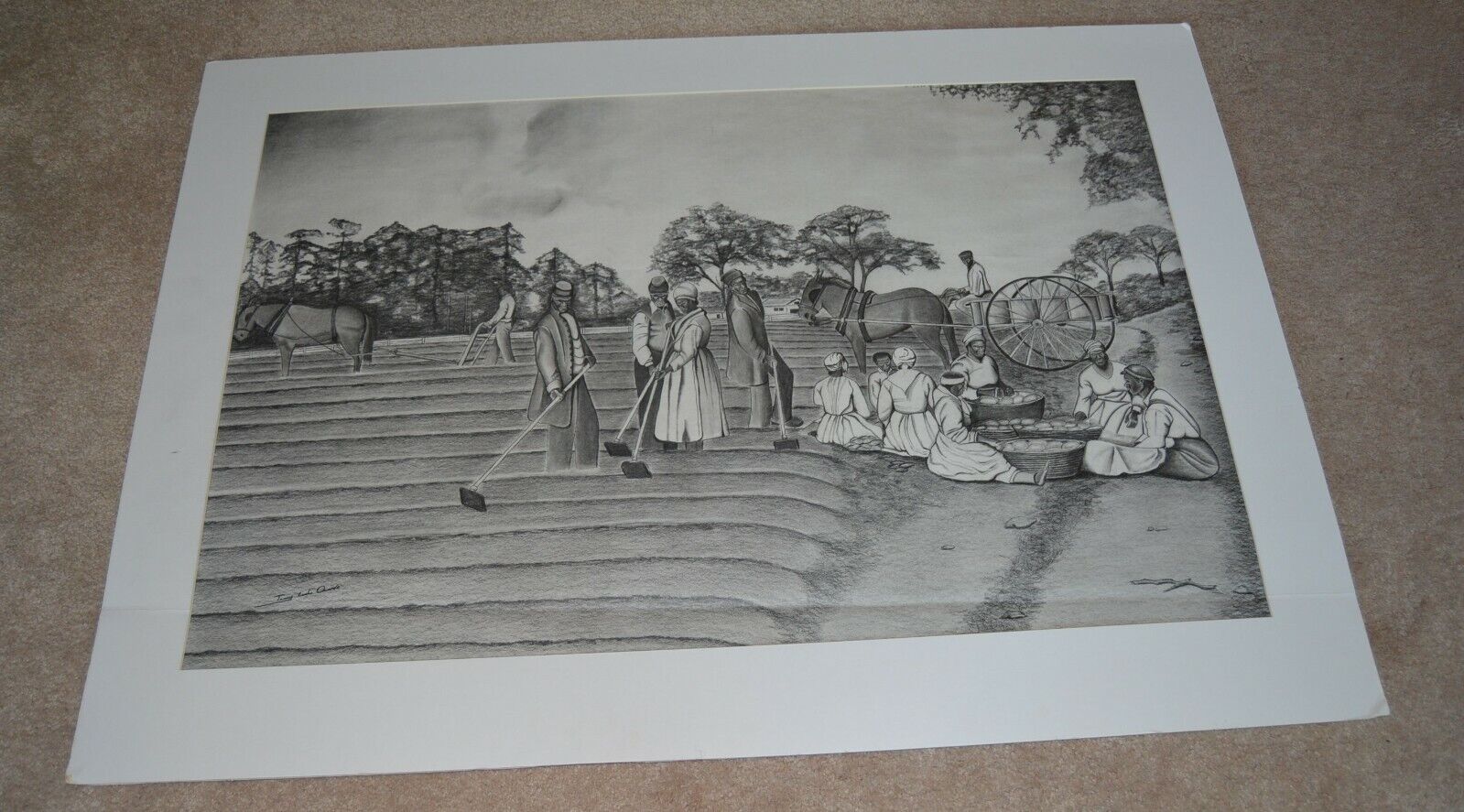

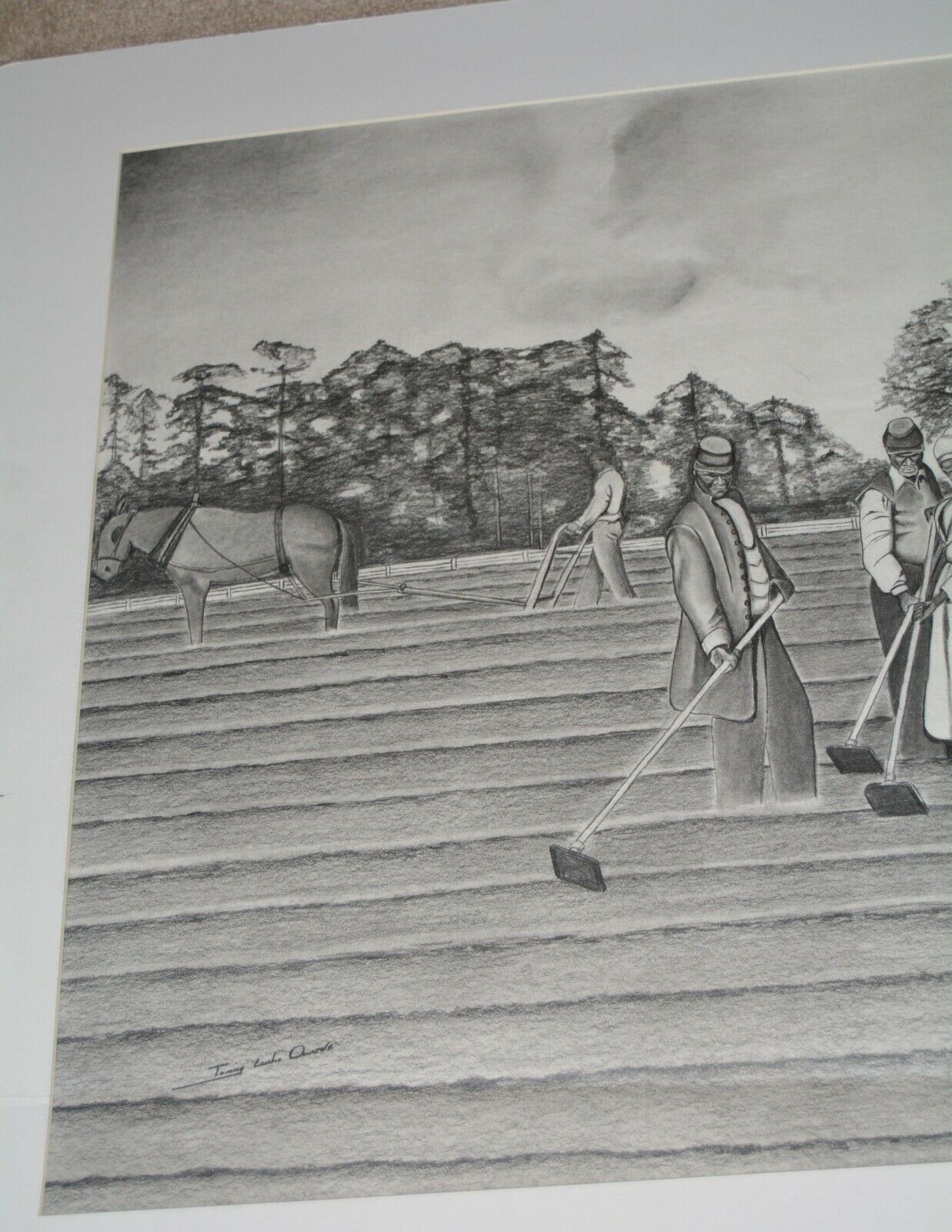

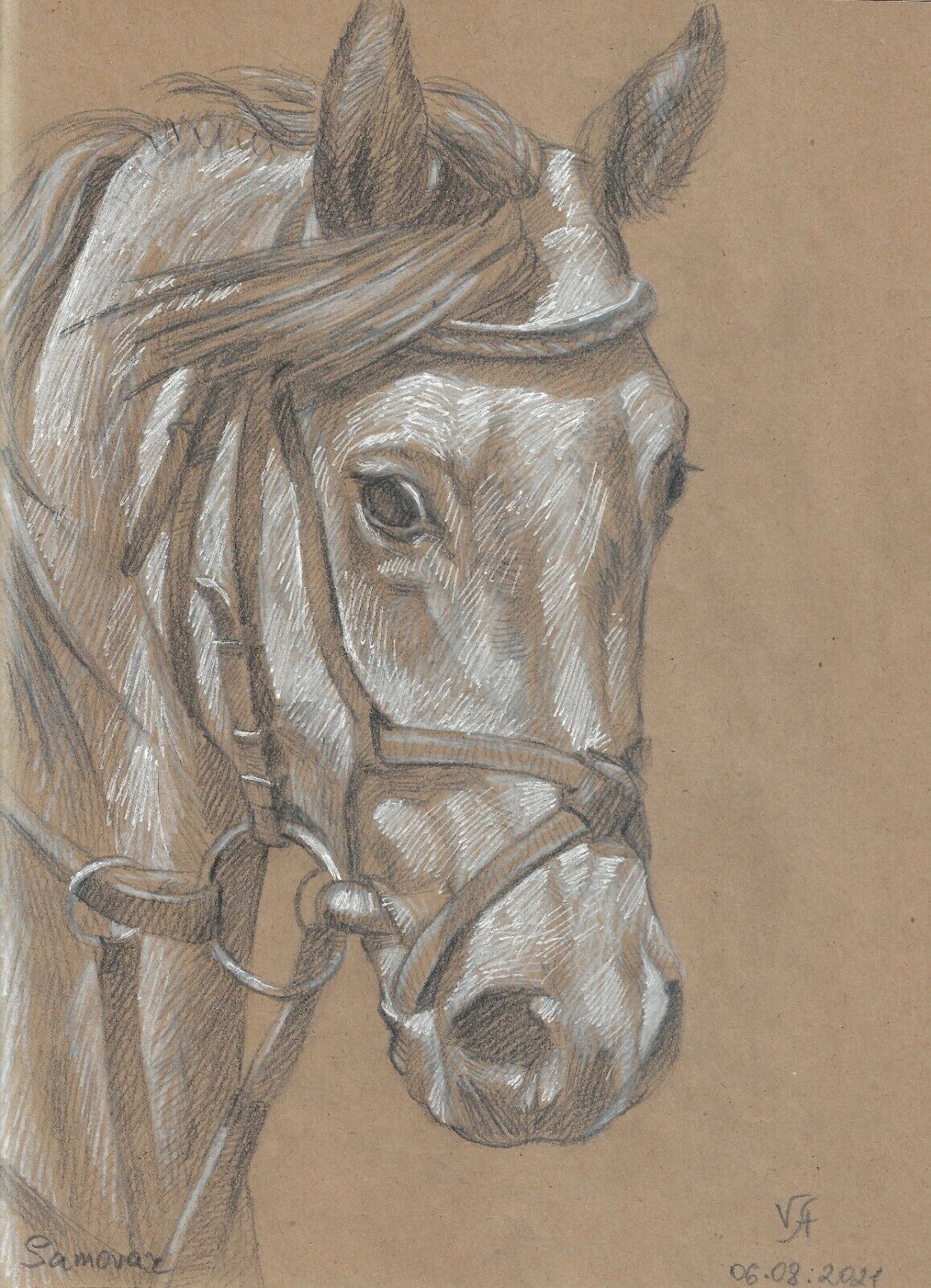

AFRICAN AMERICAN ART DRAWING TOMMY CURTIS OWENS CIVIL WAR STRUGGLING SHARE CROP

$ 316.8

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

A FANTASTIC LARGE PENCIL DRAWING BY AFRICAN AMERICAN ARTIST TOMMY CURTIS OWENS PRISON ARTIST TITLED STRUGGLING TO SHARE THE CROP. THE DRAWING NEEDS TO BE REMATTED. OVERALL MEASURES APPROXIMATELY 29 1/4 X 41 INCHES AND DRAWING MEASURES APPROXIMATELY 23 3/4 X 35 INCHES.GREAT DRAWING OF SOLDIERS AND WORKERS AFRICAN AMERICAN MEN AND WOMEN WORKING ON THE FIELD

Rehabilitation Through The Arts (RTA) was founded by Katherine Vockins in 1996 in Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York and now operates in six men's and women's, maximum and medium security New York State prisons: Sing Sing, Bedford Hills, Woodbourne, Green Haven, Fishkill and Taconic. RTA is the lead program of Prison Communities International, a 501c3 tax-exempt non-profit organization. RTA brings art workshops in theatre, music, dance, visual arts, writing and poetry behind the walls to over 230 incarcerated men and women. Mission Statement: RTA uses the transformative power of the arts to help people in prison develop skills to unlock their potential & succeed in the larger community.

Contents

1

Background

2

The Program

3

Theatrical Productions

4

Benefits and Events

5

Board Members

6

Funding

7

References

8

External links

Background

RTA began in Sing Sing with a group of men who wanted help writing and presenting a play, and has since expanded to include dance, movement, visual arts, voice, music, literature and creative writing.

RTA uses the transformative power of the arts to help people in prison develop skills to unlock their potential & succeed in the larger community.

The Program

RTA runs innovative workshops in theatre, dance, visual arts, music and creative writing. Men and women perform in workshop presentations and full-scale productions of both original and published works.

The arts develop the ability to communicate, collaborate, set goals and imagine alternate scenarios. Even in the harsh environment of prison, trust and community build. On release, many RTA alumni work in gang prevention, substance abuse and educational programs that help others make better choices in life.

Two research studies demonstrate the positive effects of RTA's program. John Jay College of Criminal Justice's 2003 study with the NYS Department of Correctional Services showed that RTA participants had fewer infractions than a control group. A 2010 study conducted by SUNY Purchase and the NYS Department of Correctional Services concluded that RTA participants complete the GED earlier in their incarceration, more RTA participants complete educational programs beyond the GED, and that after joining RTA, participants spent an almost three-fold increase in time enrolled in post-GED courses than those who did not participate.

RTA invites over 250 community guests, including family members of participants in some facilities, to its full-scale productions in Sing Sing Correctional Facility each year. These are extraordinary opportunities for the public to witness the intelligence, talent and humanity behind prison walls, and for families to see the effort their loved ones are making to change.

RTA's classes and productions are facilitated by 25 teaching artists who fan out to remote prisons across three state counties. These are professional artists and experienced teachers - most have advanced degrees and many teach in prestigious academic institutions.

To learn more or to support RTA, go to www.rta-arts.org.

Twitter: @RTA_ARTS Instagram: @rta_arts

Theatrical Productions

The following plays were produced as a part of Rehabilitation Through The Arts at Sing Sing Correctional Facility, Ossining, NY:

Twelfth Night

The Wizard of Oz

Golden Boy

Our Town

A Few Good Men

Superior Donuts

Starting Over

Macbeth

Of Mice and Men

West Side Story

Stories from the Inside Out

The N_____ Trial

Breakin' the Mummy's Code[1]

Jitney

Fine Print

12 Angry Men[2]

Stratford's Decision[3]

Reality in Motion

SLAM

Voices From Within

A Few Good Men

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

The Sacrifice

An Evening of Theatre, Four Original One-Act Plays

When We're Home

Reality in Motion

Productions Outside of Sing Sing Prison:

The Bull Pen

Two Trains Running

Jitney

Ma Rainey

The Wiz

The Odd Couple

Death of a Salesman

Same Thing Makes You Laugh, That Thing Gonna Make You Cry

Cafe of the Heart

Benefits and Events

RTA held its first New York City Benefit performance From Sing Sing to Broadway – An Evening Without Walls in June 2006 at Playwrights Horizons Theatre, with special guest performance by Charles Dutton.

RTA's November 2010 benefit "The Inside Story", directed by Connie Grappo, featured Broadway actors Lee Wilkoff and Anne Twomey, performances by RTA alumni and an exciting auction of artwork created by RTA participants behind prison walls.

Board Members

Board members of Prison Communities International are: Karin Shiel; Allison Chernow; Katherine Vockins; Suzanne Kessler; Hans Hallundbaek; Sean Dino Johnson; Jill Becker, MD; David Schmerler; Brian Steele; Ken Fields; Sheryl Baker; E. Annette Nash Govan; Mikki Shaw; Caroline Walcott

Funding

RTA is funded through foundations such as The Tow Foundation, Art for Justice Fund, a project of the Ford Foundation managed in partnership with Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, Impact100 Westchester, ArtsWestchester, Sills Family Foundation, Tikkun Olam Foundation, Stavros Niarchos Foundation, the New York State Department of Corrections & Community Supervision, the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and many individual donors.

African-American art is a broad term describing the visual arts of the American black community (African Americans). Influenced by various cultural traditions, including those of Africa, Europe and the Americas, traditional African-American art forms include the range of plastic arts, from basket weaving, pottery, and quilting to woodcarving and painting.

Contents

1

History

1.1

Pre-colonial, Antebellum and Civil War eras

1.2

Post-Civil War

1.3

The Harlem Renaissance to contemporary art

1.3.1

Mid-20th century

2

Collections of African-American art

3

See also

4

References

5

Sources

6

External links

History

Pre-colonial, Antebellum and Civil War eras

Powder horn carved by John Bush, 1754.

Harriet Powers, Bible quilt, Mixed Media. 1898.

The earliest evidence of African-American art in the United States is the work of skilled craftsmen slaves from New England. Two categories of slave craft items survive from colonial America: articles created for personal use by slaves and articles created for public use. Examples from the period between the 17th century and the early 19th century include: small drums, quilts, wrought-iron figures, baskets, ceramic vessels, and gravestones.[1][2]

Many of Africa's most skilled slave artisans were hired out by slave owners. With the consent of their masters, some slave artisans also were able to keep a small percentage of the wages earned in their free time and thereby save enough money to purchase their, and their families', freedom.[3]

The public works of art produced by slave craftsmen were an important contribution to the Colonial economy. In New England and the Mid-Atlantic colonies, slaves were apprenticed as goldsmiths, cabinetmakers, engravers, carvers portrait painters, carpenters, masons and iron workers. The construction and decoration of the Janson House built on the Hudson River in 1712 was the work of African-Americans. Many of the oldest buildings in Louisiana, South Carolina and Georgia were built by craftsmen slaves.[2]

In the mid-eighteenth century, John Bush was a powder horn carver and soldier with the Massachusetts militia fighting with the British in the French and Indian War.[4][5] Patrick H. Reason, Joshua Johnson, and Scipio Moorhead were among the earliest known portrait artists, from the period of 1773–1887. Patronage by some white families allowed for private tutorship in special cases. Many of these sponsoring whites were abolitionists. The artists received more encouragement and were better able to support themselves in cities, of which there were more in the North and border states.

Harriet Powers (1837–1910) was an African-American folk artist and quilt maker from rural Georgia, United States, born into slavery. Now nationally recognized for her quilts, she used traditional appliqué techniques to record local legends, Bible stories, and astronomical events on her quilts. Only two of her late quilts have survived: Bible Quilt 1886 and Bible Quilt 1898. Her quilts are considered among the finest examples of 19th-century Southern quilting,.[6][7]

Like Powers, the women of Gee's Bend developed a distinctive, bold, and sophisticated quilting style based on traditional American (and African-American) quilts, but with a geometric simplicity. Although widely separated by geography, they have qualities reminiscent of Amish quilts and modern art. The women of Gee's Bend passed their skills and aesthetic down through at least six generations to the present.[8] At one time scholars believed slaves sometimes utilized quilt blocks to alert other slaves about escape plans during the time of the Underground Railroad,[9] but most historians do not agree. Quilting remains alive as form of artistic expression in the African-American community.

Post-Civil War

After the Civil War, it became increasingly acceptable for African American-created works to be exhibited in museums, and artists increasingly produced works for this purpose. These were works mostly in the European romantic and classical traditions of landscapes and portraits. Edward Mitchell Bannister, Henry Ossawa Tanner and Edmonia Lewis are the most notable of this time. Others include Grafton Tyler Brown, Nelson A. Primus and Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller.[citation needed]

The goal of widespread recognition across racial boundaries was first eased within America's big cities, including Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, New York, and New Orleans. Even in these places, however, there were discriminatory limitations. Abroad, however, African Americans were much better received. In Europe — especially Paris, France — these artists could express much more freedom in experimentation and education concerning techniques outside traditional western art. Freedom of expression was much more prevalent in Paris as well as Munich and Rome to a lesser extent.[citation needed]

The Harlem Renaissance to contemporary art

[citation needed]

The Harlem Renaissance was one of the most notable movements in African-American art. Certain freedoms and ideas that were already widespread in many parts of the world at the time had begun to spread into the artistic communities United States during the 1920s. During this period notable artists included Richmond Barthé, Aaron Douglas, Lawrence Harris, Palmer Hayden, William H. Johnson, Sargent Johnson, John T. Biggers, Earle Wilton Richardson, Malvin Gray Johnson, Archibald Motley, Augusta Savage, Hale Woodruff, and photographer James Van Der Zee.[citation needed]

The establishment of the Harmon Foundation by art patron William E. Harmon in 1922 sponsored many artists through its Harmon Award and annual exhibitions. As it did with many such endeavors, the 1929 Great Depression largely ended funding for the arts for a time. While the Harmon Foundation still existed in this period, its financial support toward artists ended. The Harmon Foundation, however, continued supporting artists until 1967 by mounting exhibitions and offering funding for developing artists such as Jacob Lawrence.[10]

Midnight Golfer by Eugene J. Martin, mixed media collage on rag paper.

The US Treasury Department's Public Works of Art Project ineffectively attempted to provide support for artists in 1933. In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The WPA provided for all American artists and proved especially helpful to African-American artists. Artists and writers both gained work that helped them survive the Depression. Among them were Jacob Lawrence and Richard Wright. Politics, human and social conditions all became the subjects of accepted art forms.[citation needed]

Important cities with significant black populations and important African-American art circles included Philadelphia, Boston, San Francisco and Washington, D.C. The WPA led to a new wave of important black art professors. Mixed media, abstract art, cubism, and social realism became not only acceptable, but desirable. Artists of the WPA united to form the 1935 Harlem Artists Guild, which developed community art facilities in major cities. Leading forms of art included drawing, sculpture, printmaking, painting, pottery, quilting, weaving and photography. By 1939, the costly WPA and its projects all were terminated.[citation needed]

In 1943, James A. Porter, a professor in the Department of Art at Howard University, wrote the first major text on African-American art and artists, Modern Negro Art.[citation needed]

Mid-20th century

In the 1950s and 1960s, few African-American artists were widely known or accepted. Despite this, The Highwaymen, a loose association of 26 African-American artists from Fort Pierce, Florida, created idyllic, quickly realized images of the Florida landscape and peddled some 200,000 of them from the trunks of their cars. In the 1950s and 1960s, it was impossible to find galleries interested in selling artworks by a group of unknown, self-taught African Americans,[11] so they sold their art directly to the public rather than through galleries and art agents. Rediscovered in the mid-1990s, today they are recognized as an important part of American folk history.[12][13]

The current market price for an original Highwaymen painting can easily bring in thousands of dollars. In 2004 the original group of 26 Highwaymen were inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame.[14] Currently 8 of the 26 are deceased, including A. Hair, H. Newton, Ellis and George Buckner, A. Moran, L. Roberts, Hezekiah Baker and most recently Johnny Daniels. The full list of 26 can be found in the Florida Artists Hall of Fame, as well as various highwaymen and Florida art websites.

Jerry Harris, Dogon mother and child, constructed and carved wood with found objects, laminated clay (Bondo), and wooden dowels.

After the Second World War, some artists took a global approach, working and exhibiting abroad, in Paris, and as the decade wore on, relocated gradually in other welcoming cities such as Copenhagen, Amsterdam, and Stockholm: Barbara Chase-Riboud, Edward Clark, Harvey Cropper, Beauford Delaney, Herbert Gentry,[15] Bill Hutson, Clifford Jackson,[16] Sam Middleton,[17] Larry Potter, Haywood Bill Rivers, Merton Simpson, and Walter Williams.[18][19]

Some African-American artists did make it into important New York galleries by the 1950s and 1960s: Horace Pippin, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, William T. Williams, Norman Lewis, Thomas Sills,[20] and Sam Gilliam were among the few who had successfully been received in a gallery setting. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s led artists to capture and express the times and changes. Galleries and community art centers developed for the purpose of displaying African-American art, and collegiate teaching positions were created by and for African-American artists. Some African-American women were also active in the feminist art movement in the 1970s. Faith Ringgold made work that featured black female subjects and that addressed the conjunction of racism and sexism in the U.S., while the collective Where We At (WWA) held exhibitions exclusively featuring the artwork of African-American women.[21]

By the 1980s and 1990s, hip-hop graffiti became predominate in urban communities. Most major cities had developed museums devoted to African-American artists. The National Endowment for the Arts provided increasing support for these artists.

Kara Walker, a contemporary American artist, is known for her exploration of race, gender, sexuality, violence and identity in her artworks. Walker's silhouette images work to bridge unfinished folklore in the Antebellum South and are reminiscent of the earlier work of Harriet Powers. Her nightmarish yet fantastical images incorporate a cinematic feel. In 2007, Walker was listed among Time Magazine's "100 Most Influential People in The World, Artists and Entertainers".[22]

Textile artists are part of African-American art history. According to the 2010 Quilting in America industry survey, there are 1.6 million quilters in the United States.[23] One historic non profit organization with several members who are quilters and fiber artists is Women of Visions, Inc. located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania at the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts. WOV Inc artists past and present work in a variety of mediums. Those who have shown internationally include Renee Stout and Tina Williams Brewer.

Influential contemporary artists include Larry D. Alexander, Laylah Ali, Amalia Amaki, Emma Amos, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Dawoud Bey, Camille Billops, Mark Bradford, Edward Clark, Willie Cole, Robert Colescott, Louis Delsarte, David Driskell, Leonardo Drew, Mel Edwards, Ricardo Francis, Charles Gaines, Ellen Gallagher, Herbert Gentry, Sam Gilliam, David Hammons, Jerry Harris, Joseph Holston, Richard Hunt, Martha Jackson-Jarvis, Katie S. Mallory, M. Scott Johnson, Rashid Johnson, Joe Lewis, Glenn Ligon, James Little, Edward L. Loper, Sr., Alvin D. Loving, Kerry James Marshall, Eugene J. Martin, Richard Mayhew, Sam Middleton, Howard McCalebb, Charles McGill, Thaddeus Mosley, Sana Musasama, Senga Nengudi, Joe Overstreet, Martin Puryear, Adrian Piper, Howardena Pindell, Faith Ringgold, Gale Fulton Ross, Alison Saar, Betye Saar, John Solomon Sandridge, Raymond Saunders, John T. Scott, Joyce Scott, Gary Simmons, Lorna Simpson, Renee Stout, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, Stanley Whitney, William T. Williams, Jack Whitten, Fred Wilson, Richard Wyatt, Jr., Richard Yarde, and Purvis Young, Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas, Barkley Hendricks, Jeff Sonhouse, William Walker, Ellsworth Ausby, Che Baraka, Emmett Wigglesworth, Otto Neals, Dindga McCannon, Terry Dixon (artist), Frederick J. Brown, and many others.

Hip hop is a form of art for African Americans.[24]

Very few African American artists included black nudity in their work.[25]

Collections of African-American art

Many American museums hold works by African American artists, including Smithsonian American Art Museum[26] Colleges and universities with important collections include Fisk University, Spelman College and Howard University.[27] Other important collections of African-American art include the Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art, the Paul R. Jones collections at the University of Delaware and University of Alabama, the David C. Driskell Art collection, the Harmon and Harriet Kelley Collection of African American Art, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the Mott-Warsh collection.

See also

flag

United States portal

African-American culture

African-American literature

African-American music

Black Arts Movement

Chicano art

Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor

The Highwaymen (artists)

James A. Porter Colloquium on African American Art

List of African-American visual artists